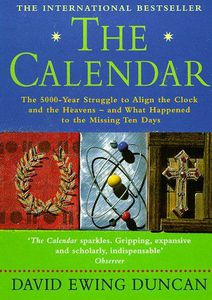

In his latest book, David Ewing Duncan traces the development of our modern-day calendar and describes how people's experiences are shaped by their conception of time. Duncan postulates that all this concern with time started when a Cro-Magnon man decided to mark off the days of the lunar cycle on an eagle bone. After recounting the slow evolution of the calendar through the centuries, the author laments how time oriented our society has become: "There are moments when I am hopelessly late, or cannot possibly fit anything else into my schedule, when I sigh and wish that Cro-Magnon man 13,000 years ago in the Dordogne Valley had set aside his eagle bone and gone to bed." The book is organized in chronological order and focuses mainly on the centuries leading up to the adoption of the Gregorian calendar (our modern calendar) by the Catholic Church in 1582. Along the way, Duncan describes the ancient calendars of many cultures all over the globe, from India to Egypt to the Mayan empire. During the Middle Ages, Christian churches discouraged scientific inquiry on the theory that it was wrong to question the nature of God's creation. This severely hampered the refinement of the calendar and the advancement of many academic pursuits. By the 16th century, Europe's calendars were 11 days out of sync with the solar year, which meant Easter was being celebrated on the wrong day. An infusion of knowledge from India and the Middle East helped Europeans get back on track. Duncan profiles the many mathematicians, philosophers, and monks who made organizing time their life's work. This book honors the efforts of those scholars and examines the way politics and religion influenced societal perceptions of time through the ages. --Jill Marquis

| Dewey |

529 |

| Cover Price |

$6.99 |

| No. of Pages |

384 |

| Height x Width |

6.9

x

5.0

inch |

|

|

|